Robust TOST Procedures

Aaron R. Caldwell

2026-01-26

robustTOST.RmdIntroduction to Robust TOST Methods

The Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure is a statistical approach used to test for equivalence between groups or conditions. Unlike traditional null hypothesis significance testing (NHST) which aims to detect differences, TOST is designed to statistically demonstrate similarity or equivalence within predefined bounds.

While the standard t_TOST function in TOSTER provides a

parametric approach to equivalence testing, it relies on assumptions of

normality and homogeneity of variance. In real-world data analysis,

these assumptions are often violated, necessitating more robust

alternatives. This vignette introduces several robust TOST methods

available in the TOSTER package that maintain their validity under a

wider range of data conditions.

When to Use Robust TOST Methods

Consider using the robust alternatives to t_TOST

when:

- Your data shows notable departures from normality (e.g., skewed distributions, heavy tails)

- Potential outliers are a concern

- Sample sizes are small or unequal

- You have concerns about violating the assumptions of parametric tests

- You want to confirm parametric test results with complementary nonparametric approaches

The following table provides a quick overview of the robust methods covered in this vignette:

| Method | Function | Key Characteristics | Best Used When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon TOST | wilcox_TOST() |

Rank-based, nonparametric | Ordinal data; see caveats below |

| Brunner-Munzel | brunner_munzel() |

Probability-based, robust to heteroscedasticity | Stochastic superiority is the effect of interest |

| Permutation t-test | perm_t_test() |

Resampling without replacement, exact p-values possible | Small samples, mean differences, exact inference |

| Bootstrap TOST | boot_t_TOST() |

Resampling with replacement, flexible | Moderate samples, mean differences, visualization |

| Log-Transformed TOST | log_TOST() |

Ratio-based, for multiplicative comparisons | Comparing relative differences (e.g., bioequivalence) |

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney TOST

The Wilcoxon group of tests (includes Mann-Whitney U-test) provide a

non-parametric test of differences between groups, or within samples,

based on ranks. This provides a test of location shift, which is a fancy

way of saying differences in the center of the distribution (i.e., in

parametric tests the location is mean). With TOST, there are two

separate tests of directional location shift to determine if the

location shift is within (equivalence) or outside (minimal effect). The

exact calculations can be explored via the documentation of the

wilcox.test function.

A Note on the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney Tests

While the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (WMW) tests are widely used as the “non-parametric alternative” to the t-test, there are reasons to be cautious about their interpretation. As Karch (2021) discusses, the WMW tests do not straightforwardly test hypotheses about means or medians. The null hypothesis being tested is that the two distributions are identical, and when this null is rejected, interpreting what differs between groups (location? scale? shape?) can be ambiguous.

This interpretive difficulty becomes even more pronounced in the equivalence testing context. When we perform TOST with Wilcoxon tests, we are testing whether a location shift parameter falls within equivalence bounds, but the relationship between this parameter and familiar quantities like means or medians depends on assumptions about distributional shape that may not hold.

Recommendation: If your goal is to make inferences

about differences in means (or trimmed means), you are better served by

the resampling methods described later in this vignette:

perm_t_test or boot_t_TOST. These methods test

hypotheses directly about means while relaxing distributional

assumptions. If your interest is in stochastic superiority (the

probability that a randomly selected observation from one group exceeds

one from another), the Brunner-Munzel test provides a clearer framework

with an interpretable effect size.

The wilcox_TOST function remains available for

situations where rank-based tests are specifically desired, such as with

ordinal data or when you want consistency with prior analyses that used

WMW tests.

Key Features and Usage

TOSTER’s version is the wilcox_TOST function. Overall,

this function operates extremely similar to the t_TOST

function. However, the standardized mean difference (SMD) is

not calculated. Instead the rank-biserial correlation is

calculated for all types of comparisons (e.g., two sample, one

sample, and paired samples). Also, there is no plotting capability at

this time for the output of this function.

The wilcox_TOST function is particularly useful

when:

- You’re working with ordinal data

- You’re concerned about outliers influencing your results

- You need a test that makes minimal assumptions about the underlying distributions

Understanding the Equivalence Bounds (eqb)

The equivalence bounds (eqb) are specified on the

raw scale of your data, just like the mu

argument in stats::wilcox.test(). This means

eqb represents actual differences in location (e.g.,

location shifts) in the original units of measurement, not standardized

effect sizes. Unlike t_TOST, where eqb

can be set in terms of standardized mean differences (e.g.,

Cohen’s d), in wilcox_TOST, you must define

eqb based on the scale of your data for

wilcox_TOST.

The eqb and ses parameters are

completely independent:

-

eqbsets the equivalence bounds on the raw data scale for the statistical test -

sesonly determines which type of standardized effect size is calculated and reported (e.g., rank-biserial correlation, concordance probability, or odds) - Changing

sesdoes not change the meaning or interpretation ofeqb

As an example, we can use the sleep data to make a non-parametric comparison of equivalence.

data('sleep')

library(TOSTER)

test1 = wilcox_TOST(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

eqb = .5)

print(test1)##

## Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant W = 20.000, p = 8.94e-01

## The null hypothesis test was non-significant W = 25.500, p = 6.93e-02

## NHST: don't reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to zero

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## Test Statistic p.value

## NHST 25.5 0.069

## TOST Lower 34.0 0.894

## TOST Upper 20.0 0.013

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate C.I. Conf. Level

## Median of Differences -1.346 [-3.4, -0.1] 0.9

## Rank-Biserial Correlation -0.490 [-0.7493, -0.1005] 0.9Interpreting the Results

When interpreting the output of wilcox_TOST, pay

attention to:

- The p-values for both one-sided tests (

p1andp2) - The equivalence test p-value (

TOSTp), which should be < alpha to claim equivalence - The rank-biserial correlation (

rb) and its confidence interval

A statistically significant equivalence test (p < alpha) indicates that the observed effect is statistically within your specified equivalence bounds. The rank-biserial correlation provides a measure of effect size, with values ranging from -1 to 1:

- Values near 0 indicate negligible association

- Values around ±0.3 indicate a small effect

- Values around ±0.5 indicate a moderate effect

- Values around ±0.7 or greater indicate a large effect

Rank-Biserial Correlation

The standardized effect size reported for the

wilcox_TOST procedure is the rank-biserial correlation.

This is a fairly intuitive measure of effect size which has the same

interpretation of the common language effect size (Kerby 2014). However, instead of assuming

normality and equal variances, the rank-biserial correlation calculates

the number of favorable (positive) and unfavorable (negative) pairs

based on their respective ranks.

For the two sample case, the correlation is calculated as the proportion of favorable pairs minus the unfavorable pairs.

\[ r_{biserial} = f_{pairs} - u_{pairs} \]

Where: - \(f_{pairs}\) is the proportion of favorable pairs - \(u_{pairs}\) is the proportion of unfavorable pairs

For the one sample or paired samples cases, the correlation is calculated with ties (values equal to zero) not being dropped. This provides a conservative estimate of the rank biserial correlation.

It is calculated in the following steps wherein \(z\) represents the values or difference between paired observations:

- Calculate signed ranks:

\[ r_j = -1 \cdot sign(z_j) \cdot rank(|z_j|) \]

Where: - \(r_j\) is the signed rank for observation \(j\) - \(sign(z_j)\) is the sign of observation \(z_j\) (+1 or -1) - \(rank(|z_j|)\) is the rank of the absolute value of observation \(z_j\)

- Calculate the positive and negative sums:

\[ R_{+} = \sum_{1\le i \le n, \space z_i > 0}r_j \]

\[ R_{-} = \sum_{1\le i \le n, \space z_i < 0}r_j \]

Where: - \(R_{+}\) is the sum of ranks for positive observations - \(R_{-}\) is the sum of ranks for negative observations

- Determine the smaller of the two rank sums:

\[ T = min(R_{+}, \space R_{-}) \]

\[ S = \begin{cases} -4 & R_{+} \ge R_{-} \\ 4 & R_{+} < R_{-} \end{cases} \]

Where: - \(T\) is the smaller of the two rank sums - \(S\) is a sign factor based on which rank sum is smaller

- Calculate rank-biserial correlation:

\[ r_{biserial} = S \cdot | \frac{\frac{T - \frac{(R_{+} + R_{-})}{2}}{n}}{n + 1} | \]

Where: - \(n\) is the number of observations (or pairs) - The final value ranges from -1 to 1

Confidence Intervals

The Fisher approximation is used to calculate the confidence intervals.

For paired samples, or one sample, the standard error is calculated as the following:

\[ SE_r = \sqrt{ \frac {(2 \cdot nd^3 + 3 \cdot nd^2 + nd) / 6} {(nd^2 + nd) / 2} } \]

wherein, nd represents the total number of observations (or pairs).

For independent samples, the standard error is calculated as the following:

\[ SE_r = \sqrt{\frac {(n1 + n2 + 1)} { (3 \cdot n1 \cdot n2)}} \]

Where:

- \(n1\) and \(n2\) are the sample sizes of the two groups

The confidence intervals can then be calculated by transforming the estimate.

\[ r_z = atanh(r_{biserial}) \]

Then the confidence interval can be calculated and back transformed.

\[ r_{CI} = tanh(r_z \pm Z_{(1 - \alpha / 2)} \cdot SE_r) \]

Where:

- \(Z_{(1 - \alpha / 2)}\) is the critical value from the standard normal distribution

- \(\alpha\) is the significance level (typically 0.05)

Conversion to other effect sizes

Two other effect sizes can be calculated for non-parametric tests. First, there is the concordance probability, which is also known as the c-statistic, c-index, or probability of superiority1. The c-statistic is converted from the correlation using the following formula:

\[ c = \frac{(r_{biserial} + 1)}{2} \]

The c-statistic can be interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected observation from one group will be greater than a randomly selected observation from another group. A value of 0.5 indicates no difference between groups, while values approaching 1 indicate perfect separation between groups.

The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney odds (O’Brien and Castelloe 2006), also known as the “Generalized Odds Ratio” (Agresti 1980), is calculated by converting the c-statistic using the following formula:

\[ WMW_{odds} = e^{logit(c)} \]

Where \(logit(c) = \ln\frac{c}{1-c}\)

The WMW odds can be interpreted similarly to a traditional odds ratio, representing the odds that an observation from one group is greater than an observation from another group.

Either effect size is available by simply modifying the

ses argument for the wilcox_TOST function.

Note: In all examples below, eqb = .5

remains on the raw data scale (the scale of the extra

variable in hours of sleep). The ses argument only changes

which standardized effect size is calculated and reported; it does not

change the equivalence bounds or the hypothesis test itself.

# Rank biserial

wilcox_TOST(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

ses = "r",

eqb = .5)##

## Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant W = 20.000, p = 8.94e-01

## The null hypothesis test was non-significant W = 25.500, p = 6.93e-02

## NHST: don't reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to zero

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## Test Statistic p.value

## NHST 25.5 0.069

## TOST Lower 34.0 0.894

## TOST Upper 20.0 0.013

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate C.I. Conf. Level

## Median of Differences -1.346 [-3.4, -0.1] 0.9

## Rank-Biserial Correlation -0.490 [-0.7493, -0.1005] 0.9

# Odds

wilcox_TOST(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

ses = "o",

eqb = .5)##

## Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant W = 20.000, p = 8.94e-01

## The null hypothesis test was non-significant W = 25.500, p = 6.93e-02

## NHST: don't reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to zero

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## Test Statistic p.value

## NHST 25.5 0.069

## TOST Lower 34.0 0.894

## TOST Upper 20.0 0.013

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate C.I. Conf. Level

## Median of Differences -1.3464 [-3.4, -0.1] 0.9

## WMW Odds 0.3423 [0.1433, 0.8173] 0.9

# Concordance

wilcox_TOST(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

ses = "c",

eqb = .5)##

## Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant W = 20.000, p = 8.94e-01

## The null hypothesis test was non-significant W = 25.500, p = 6.93e-02

## NHST: don't reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to zero

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## Test Statistic p.value

## NHST 25.5 0.069

## TOST Lower 34.0 0.894

## TOST Upper 20.0 0.013

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate C.I. Conf. Level

## Median of Differences -1.346 [-3.4, -0.1] 0.9

## Concordance 0.255 [0.1254, 0.4497] 0.9Guidelines for Selecting Effect Size Measures

-

Rank-biserial correlation (

"r") is useful when you want a correlation-like measure that’s easily interpretable and comparable to other correlation coefficients. -

Concordance probability (

"c") is beneficial when you want to express the effect in terms of probability, making it accessible to non-statisticians. -

WMW odds (

"o") is helpful when you want to express the effect in terms familiar to those who work with odds ratios in logistic regression or epidemiology.

Brunner-Munzel Test

As Karch (2021) explained, there are some reasons to dislike the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (WMW) family of tests as the non-parametric alternative to the t-test. Regardless of the underlying statistical arguments2, it can be argued that the interpretation of the WMW tests, especially when involving equivalence testing, is difficult. Some may want a non-parametric alternative to the WMW test, and the Brunner-Munzel test(s) may be a useful option.

Overview and Advantages

The Brunner-Munzel test (Brunner & Munzel, 2000; Neubert & Brunner, 2007) offers several advantages over the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests:

- It does not assume equal distributions (shapes) between groups

- It is robust to heteroscedasticity (unequal variances)

- It provides a more interpretable effect size measure (the “relative effect”)

- It maintains good statistical properties even with unequal sample sizes

The Brunner-Munzel test is based on calculating the “stochastic superiority” (Karch, 2021), which is usually referred to as the relative effect, based on the ranks of the two groups being compared (X and Y). A Brunner-Munzel type test is then a directional test of an effect, and answers a question akin to “what is the probability that a randomly sampled value of X will be greater than Y?”

\[ \hat p = P(X>Y) + 0.5 \cdot P(X=Y) \]

Where:

- \(P(X>Y)\) is the probability that a random value from X exceeds a random value from Y

- \(P(X=Y)\) is the probability that random values from X and Y are equal

- The 0.5 factor means ties contribute half their weight to the probability

The relative effect \(\hat p\) has an intuitive interpretation:

- \(\hat p = 0.5\) indicates no difference between groups (stochastic equality)

- \(\hat p > 0.5\) indicates values in X tend to be greater than values in Y

- \(\hat p < 0.5\) indicates values in X tend to be smaller than values in Y

Basics of the Calculative Approach

A studentized test statistic can be calculated as:

\[ t = \sqrt{N} \cdot \frac{\hat p - p_{null}}{s} \]

Where:

- \(N\) is the total sample size

- \(\hat p\) is the estimated relative effect

- \(p_{null}\) is the null hypothesis value (typically 0.5)

- \(s\) is the rank-based Brunner-Munzel standard error

The default null hypothesis \(p_{null}\) is typically 0.5 (50% probability of superiority is the default null), and \(s\) refers to the rank-based Brunner-Munzel standard error. The null can be modified, thereby allowing for equivalence testing directly based on the relative effect. Additionally, for paired samples the probability of superiority is based on a hypothesis of exchangeability and is not based on the difference scores3.

For more details on the calculative approach, I suggest reading Karch

(2021). At small sample sizes, it is recommended that the permutation

version of the test (test_method = "perm") be used rather

than the basic test statistic approach.

Test Methods

The brunner_munzel function provides three test methods

via the test_method argument:

“t” (default): Uses a t-distribution approximation with Satterthwaite-Welch degrees of freedom. This is appropriate for moderate to large sample sizes (generally n ≥ 15 per group).

“logit”: Uses a logit transformation to produce range-preserving confidence intervals that are guaranteed to stay within [0, 1]. This method is recommended when the estimated relative effect is close to 0 or 1.

“perm”: A studentized permutation test following Neubert & Brunner (2007). This method is highly recommended when sample sizes are small (< 15 per group) as it provides better control of Type I error rates in these situations.

Examples

Basic Two-Sample Test

The interface for the function is similar to t.test. The

brunner_munzel function allows for standard hypothesis

tests (“two.sided”, “less”, “greater”) as well as equivalence and

minimal effect tests.

# Default studentized test (t-approximation)

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep)## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel test

##

## data: extra by group

## t = -2.1447, df = 16.898, p-value = 0.04682

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.01387048 0.49612952

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255

# Permutation test (recommended for small samples)

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

test_method = "perm")##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel permutation test

##

## data: extra by group

## t-observed = -2.1447, N-permutations = 10000, p-value = 0.05759

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.002350991 0.509492242

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255Logit Transformation for Range-Preserving CIs

When the relative effect estimate is close to 0 or 1, the standard confidence intervals may extend beyond the valid [0, 1] range. The logit transformation method addresses this:

# Logit transformation for range-preserving CIs

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

test_method = "logit")## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel test (logit)

##

## data: extra by group

## t = -1.7829, df = 16.898, p-value = 0.09257

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.08775255 0.54912824

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255Equivalence Testing

The brunner_munzel function directly supports

equivalence testing via the alternative argument. For

equivalence tests, you specify bounds for the relative effect using the

mu argument:

# Equivalence test: is the relative effect between 0.3 and 0.7?

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "equivalence",

mu = c(0.3, 0.7))## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel test

##

## data: extra by group

## t = -0.39392, df = 16.898, p-value = 0.6507

## alternative hypothesis: equivalence

## null values:

## lower bound upper bound

## 0.3 0.7

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## 0.0562039 0.4537961

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255

# Permutation-based equivalence test

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "equivalence",

mu = c(0.3, 0.7),

test_method = "perm")## NOTE: Permutation-based TOST for equivalence/minimal.effect testing.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel permutation test

##

## data: extra by group

## t-observed = -0.39392, N-permutations = 10000, p-value = 0.6546

## alternative hypothesis: equivalence

## null values:

## lower bound upper bound

## 0.3 0.7

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## 0.05668902 0.45331098

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255Minimal Effect Testing

You can also test whether the relative effect falls outside specified bounds (minimal effect test):

# Minimal effect test: is the relative effect outside 0.4 to 0.6?

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "minimal.effect",

mu = c(0.4, 0.6))## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel test

##

## data: extra by group

## t = -1.2693, df = 16.898, p-value = 0.1108

## alternative hypothesis: minimal.effect

## null values:

## lower bound upper bound

## 0.4 0.6

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## 0.0562039 0.4537961

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255Paired Samples

The Brunner-Munzel test can also be applied to paired samples using

the paired argument. Note that for paired samples, the test

is based on a hypothesis of exchangeability:

# Paired samples test

brunner_munzel(x = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1],

y = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2],

paired = TRUE)## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Exact paired Brunner-Munzel test

##

## data: sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1] and sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2]

## t = -3.7266, df = 9, p-value = 0.004722

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.1062776 0.4037224

## sample estimates:

## P(X>Y) + .5*P(X=Y)

## 0.255

# Paired samples with permutation test

brunner_munzel(x = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1],

y = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2],

paired = TRUE,

test_method = "perm")##

## Paired Brunner-Munzel permutation test

##

## data: sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1] and sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2]

## t-observed = -3.7266, N-permutations = 1024, p-value = 0.003906

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is not equal to 0.5

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.1233862 0.3866138

## sample estimates:

## P(X>Y) + .5*P(X=Y)

## 0.255Testing Against a Non-Standard Null

You can test against null values other than 0.5:

# Test if the relative effect differs from 0.3

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

mu = 0.3)## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel test

##

## data: extra by group

## t = -0.39392, df = 16.898, p-value = 0.6986

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is not equal to 0.3

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.01387048 0.49612952

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255Interpreting Brunner-Munzel Results

When interpreting the Brunner-Munzel test results:

- The relative effect (p-hat) is the primary measure of interest

- Values near 0.5 suggest no tendency for one group to produce larger values than the other

- For equivalence testing, you are testing whether this relative effect falls within your specified bounds

- A significant equivalence test suggests that the probability of superiority is statistically confined to your specified range

Choosing the Right Test Method

Use test_method = "t" when:

- Sample sizes are moderate to large (n ≥ 15 per group)

- You want the fastest computation

- The relative effect estimate is not near the boundaries (0 or 1)

Use test_method = "logit" when:

- The relative effect estimate is close to 0 or 1

- You need confidence intervals guaranteed to stay within [0, 1]

- Sample sizes are moderate to large

Use test_method = "perm" when:

- Sample sizes are small (n < 15 per group)

- You want better Type I error control in small samples

- Precision is more important than computational speed

Note that the permutation approach can be computationally intensive for large datasets. Additionally, with a permutation test you may observe situations where the confidence interval and the p-value would yield different conclusions.

Non-Inferiority Testing

The Brunner-Munzel test can be used for non-inferiority testing in clinical trials with ordered categorical data (Munzel & Hauschke, 2003). By setting appropriate bounds, you can test whether a new treatment is not relevantly inferior to a standard:

# Example: test non-inferiority with lower bound of 0.35

# (i.e., the new treatment should not be substantially worse)

brunner_munzel(formula = extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "greater",

mu = 0.35)## Sample size in at least one group is small. Permutation test (test_method = 'perm') is highly recommended.##

## Two-sample Brunner-Munzel test

##

## data: extra by group

## t = -0.83161, df = 16.898, p-value = 0.7914

## alternative hypothesis: true relative effect is greater than 0.35

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.0562039 1.0000000

## sample estimates:

## P(1>2) + .5*P(1=2)

## 0.255Resampling Methods: Bootstrapping and Permutation

Resampling methods provide robust alternatives to parametric t-tests by using the data itself to approximate the sampling distribution of the test statistic. TOSTER offers two complementary resampling approaches: bootstrapping and permutation testing. While both methods relax distributional assumptions, they differ in their mechanics and are suited to different situations.

Conceptual Overview

Bootstrapping resamples with replacement from the observed data to estimate the variability of a statistic. The bootstrap distribution approximates what we would see if we could repeatedly sample from the true population. This approach is particularly useful when you want confidence intervals and effect size estimates alongside your p-values.

Permutation testing resamples without replacement by randomly reassigning observations to groups (or flipping signs for one-sample/paired tests). Under the null hypothesis of no difference, group labels are exchangeable, and the permutation distribution represents the exact null distribution. Permutation tests provide valid inference even with very small samples where asymptotic approximations may fail.

When to Use Each Method

| Scenario | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Very small samples (paired/one-sample N < 17, two-sample N < 20) | Permutation | Exact permutations are computationally feasible and provide exact p-values |

| Moderate to large samples | Bootstrap | More computationally efficient; provides stable CI estimates |

| Outliers present | Permutation with trimming | Combines exact inference with robust location estimation |

| Complex data structures | Bootstrap | More flexible for non-standard designs |

| Publication requiring exact p-values | Permutation (if feasible) | No Monte Carlo error when exact permutations computed |

The sample size thresholds above reflect computational practicality. For one-sample or paired tests, the number of possible sign permutations is \(2^n\), which equals 65,536 when n = 16 and jumps to 131,072 at n = 17. For two-sample tests, the number of possible group assignments is \(\binom{n_x + n_y}{n_x}\), which grows even faster. When exact enumeration is feasible, permutation tests yield exact p-values with no Monte Carlo error.

Permutation t-test

The perm_t_test function implements studentized

permutation tests following the approaches of Janssen (1997) and Chung

and Romano (2013). The studentized approach computes a

t-statistic for each permutation, making the test valid even under

heteroscedasticity (unequal variances).

Permutation Procedure

For one-sample and paired tests, permutation is performed by randomly flipping the signs of the centered observations (or difference scores). Under the null hypothesis that the mean equals the hypothesized value, positive and negative deviations are equally likely, making sign assignments exchangeable.

For two-sample tests, permutation is performed by randomly reassigning observations to the two groups. Under the null hypothesis of no group difference, group membership is arbitrary, making the labels exchangeable.

Two-Sample Permutation Algorithm

The studentized permutation test for two independent samples proceeds as follows:

- Compute the observed test statistic from the original data. For the standard case (no trimming, unequal variances allowed):

\[ t_{obs} = \frac{\bar{x} - \bar{y} - \mu_0}{\sqrt{s_x^2/n_x + s_y^2/n_y}} \]

Where \(\bar{x}\) and \(\bar{y}\) are the sample means, \(s_x^2\) and \(s_y^2\) are the sample variances, \(n_x\) and \(n_y\) are the sample sizes, and \(\mu_0\) is the null hypothesis value (typically 0).

Pool the observations: \(z = (x_1, \ldots, x_{n_x}, y_1, \ldots, y_{n_y})\)

-

For each permutation \(b = 1, \ldots, B\):

- Randomly assign \(n_x\) observations to group X and the remaining \(n_y\) to group Y

- Compute the permutation means \(\bar{x}^{*b}\) and \(\bar{y}^{*b}\)

- Compute the permutation variances \(s_x^{*2b}\) and \(s_y^{*2b}\)

- Compute the permutation test statistic:

\[ t^{*b} = \frac{\bar{x}^{*b} - \bar{y}^{*b}}{\sqrt{s_x^{*2b}/n_x + s_y^{*2b}/n_y}} \]

- Compute the p-value as the proportion of permutation statistics as extreme as or more extreme than the observed statistic.

Welch Variant (var.equal = FALSE)

When var.equal = FALSE (the default), the standard error

is computed separately for each group as shown above. This is the

studentized permutation approach of Janssen

(1997) and Chung and Romano (2013),

which remains valid even when the two populations have different

variances.

Pooled Variance Variant (var.equal = TRUE)

When var.equal = TRUE, a pooled variance estimate is

used:

\[ s_p^2 = \frac{(n_x - 1)s_x^2 + (n_y - 1)s_y^2}{n_x + n_y - 2} \]

\[ t_{obs} = \frac{\bar{x} - \bar{y} - \mu_0}{s_p\sqrt{1/n_x + 1/n_y}} \]

The same pooled approach is applied to each permutation sample.

Yuen Variant (tr > 0)

When tr > 0, the function uses trimmed means and

winsorized variances. Let \(g = \lfloor \gamma

\cdot n \rfloor\) be the number of observations trimmed from each

tail (where \(\gamma\) is the trimming

proportion), and let \(h = n - 2g\) be

the effective sample size.

The trimmed mean is:

\[ \bar{x}_t = \frac{1}{h} \sum_{i=g+1}^{n-g} x_{(i)} \]

where \(x_{(i)}\) denotes the \(i\)-th order statistic.

The winsorized variance \(s_w^2\) is computed by replacing the \(g\) smallest values with the \((g+1)\)-th smallest and the \(g\) largest with the \((n-g)\)-th largest, then computing the usual variance.

The standard error for Yuen’s test is:

\[ SE = \sqrt{\frac{(n_x - 1) s_{w,x}^2}{h_x(h_x - 1)} + \frac{(n_y - 1) s_{w,y}^2}{h_y(h_y - 1)}} \]

The test statistic becomes:

\[ t_{obs} = \frac{\bar{x}_t - \bar{y}_t - \mu_0}{SE} \]

This same procedure is applied to each permutation sample, using trimmed means and winsorized variances computed from the permuted data.

Studentized Permutation: The perm_se Argument

By default, perm_t_test uses the

studentized permutation approach

(perm_se = TRUE), which recalculates the standard error for

each permutation sample. This follows the recommendations of Janssen (1997) and Chung

and Romano (2013), who showed that studentized permutation tests

maintain valid Type I error control even under heteroscedasticity

(unequal variances).

How perm_se and var.equal

interact:

These two arguments control different aspects of the test:

-

var.equalcontrols how the standard error is calculated (pooled vs. Welch formula) -

perm_secontrols whether the standard error is recalculated for each permutation

perm_se |

var.equal |

Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| TRUE | TRUE | Recalculates pooled variance for each permutation |

| TRUE | FALSE | Recalculates separate (Welch) variances for each permutation |

| FALSE | TRUE | Uses original pooled SE for all permutations |

| FALSE | FALSE | Uses original Welch SE for all permutations |

Recommendations:

-

Use

perm_se = TRUE(default) in most situations. The studentized approach provides better Type I error control, especially when variances differ between groups. -

Use

perm_se = FALSEonly when you are confident that variances are truly equal and want faster computation. This is the traditional (non-studentized) permutation approach, which assumes homoscedasticity. - The choice of

var.equalshould be based on your substantive knowledge about whether the groups have equal variances. When in doubt, use the defaultvar.equal = FALSE.

Combining Permutation with Trimmed Means

A key feature of perm_t_test is its support for trimmed

means via the tr argument. When tr > 0, the

function uses Yuen’s approach: trimmed means for location estimation and

winsorized variances for standard error calculation. This combination is

particularly powerful because it provides robustness against outliers

(through trimming) together with exact or near-exact inference (through

permutation).

Trimming is helpful when:

- Data contain outliers or extreme values that would unduly influence the mean

- Distributions have heavy tails

- You want robust location estimates without sacrificing the exactness of permutation inference

A common choice is tr = 0.1 (10% trimming) or

tr = 0.2 (20% trimming), though the optimal amount depends

on the suspected degree of contamination.

Example: Basic Permutation Test

data('sleep')

# Two-sample permutation t-test

perm_result <- perm_t_test(extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

R = 1999)

perm_result##

## Monte Carlo Permutation Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: extra by group

## t-observed = -1.8608, df = 17.776, p-value = 0.0785

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -3.28 0.14

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 0.75 2.33Example: Permutation Test with Trimming

When outliers are a concern, combining permutation with trimming provides doubly robust inference:

# Simulate data with outliers

set.seed(42)

x <- c(rnorm(18, mean = 0), 8, 12) # Two outliers

y <- rnorm(20, mean = 0)

# Standard permutation test (sensitive to outliers)

perm_t_test(x, y, R = 999)## Note: Number of permutations (R = 999) is less than 1000. Consider increasing R for more stable p-value estimates.##

## Monte Carlo Permutation Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: x and y

## t-observed = 1.8777, df = 23.773, p-value = 0.053

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.0004404028 2.9218589227

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 1.2479377 -0.2081052

# Trimmed permutation test (robust to outliers)

perm_t_test(x, y, tr = 0.1, R = 999)## Note: Number of permutations (R = 999) is less than 1000. Consider increasing R for more stable p-value estimates.##

## Monte Carlo Permutation Welch Yuen Two Sample t-test

##

## data: x and y

## t-observed = 1.8462, df = 29.997, p-value = 0.078

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -0.0636125 1.6437612

## sample estimates:

## trimmed mean of x trimmed mean of y

## 0.5627544 -0.1972272Example: Equivalence Testing with Permutation

The perm_t_test function supports TOSTER’s equivalence

and minimal effect alternatives:

# Equivalence test: is the effect within ±3 units?

perm_t_test(extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "equivalence",

mu = c(-3, 3),

R = 999)## Note: Number of permutations (R = 999) is less than 1000. Consider increasing R for more stable p-value estimates.##

## Monte Carlo Permutation Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: extra by group

## t-observed = 1.6724, df = 17.776, p-value = 0.051

## alternative hypothesis: equivalence

## null values:

## difference in means difference in means

## -3 3

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## -3.060 -0.138

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 0.75 2.33Exact vs. Monte Carlo Permutations

When the total number of possible permutations is less than or equal

to R, the function automatically computes all exact

permutations and prints a message. For example, with a paired sample of

n = 10, there are \(2^{10} = 1024\)

possible sign permutations, so requesting R = 1999 would

trigger exact computation.

# Small paired sample - exact permutations will be computed

before <- c(5.1, 4.8, 6.2, 5.7, 6.0, 5.5, 4.9, 5.8)

after <- c(5.6, 5.2, 6.7, 6.1, 6.5, 5.8, 5.3, 6.2)

perm_t_test(x = before, y = after,

paired = TRUE,

alternative = "less",

R = 999)## Computing all 256 exact permutations.##

## Exact Permutation Paired t-test

##

## data: before and after

## t-observed = -17, df = 7, p-value = 0.003891

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is less than 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -Inf -0.3875

## sample estimates:

## mean of the differences

## -0.425Bootstrap t-test

The boot_t_TOST function provides bootstrap-based

inference using the percentile bootstrap approach outlined by Efron and Tibshirani (1993) (see chapter 16).

The bootstrapped p-values are derived from the studentized version of a

test of mean differences. Overall, the results should be similar to

t_TOST but with greater robustness to distributional

violations.

Advantages of Bootstrapping

Bootstrap methods offer several advantages for equivalence testing:

- They make minimal assumptions about the underlying data distribution

- They are robust to deviations from normality

- They provide realistic confidence intervals even with small samples

- They can handle complex data structures and dependencies

- They often provide more accurate results when parametric assumptions are violated

Bootstrap Algorithm (Two-Sample Case)

-

Form B bootstrap data sets from x* and y* wherein x* is sampled with replacement from \(\tilde x_1,\tilde x_2, ... \tilde x_n\) and y* is sampled with replacement from \(\tilde y_1,\tilde y_2, ... \tilde y_n\)

Where:

- B is the number of bootstrap replications (set using the

Rparameter) - \(\tilde x_i\) and \(\tilde y_i\) represent the original observations in each group

- B is the number of bootstrap replications (set using the

t is then evaluated on each sample, but the mean of each sample (y or x) and the overall average (z) are subtracted from each

\[ t(z^{*b}) = \frac {(\bar x^*-\bar x - \bar z) - (\bar y^*-\bar y - \bar z)}{\sqrt {sd_y^*/n_y + sd_x^*/n_x}} \]

Where:

- \(\bar x^*\) and \(\bar y^*\) are the means of the bootstrap samples

- \(\bar x\) and \(\bar y\) are the means of the original samples

- \(\bar z\) is the overall mean

- \(sd_x^*\) and \(sd_y^*\) are the standard deviations of the bootstrap samples

- \(n_x\) and \(n_y\) are the sample sizes

- An approximate p-value can then be calculated as the number of bootstrapped results greater than the observed t-statistic from the sample.

\[ p_{boot} = \frac {\#t(z^{*b}) \ge t_{sample}}{B} \]

Where: - \(\#t(z^{*b}) \ge t_{sample}\) is the count of bootstrap t-statistics that exceed the observed t-statistic - B is the total number of bootstrap replications

The same process is completed for the one sample case but with the one sample solution for the equation outlined by \(t(z^{*b})\). The paired sample case in this bootstrap procedure is equivalent to the one sample solution because the test is based on the difference scores.

Choosing the Number of Bootstrap Replications

When using bootstrap methods, the choice of replications (the

R parameter) is important:

- R = 999 or 1999: Recommended for standard analyses

- R = 4999 or 9999: Recommended for publication-quality results or when precise p-values are needed

- R < 500: Acceptable only for exploratory analyses or when computational resources are limited

Larger values of R provide more stable results but increase computation time. For most purposes, 999 or 1999 replications strike a good balance between precision and computational efficiency.

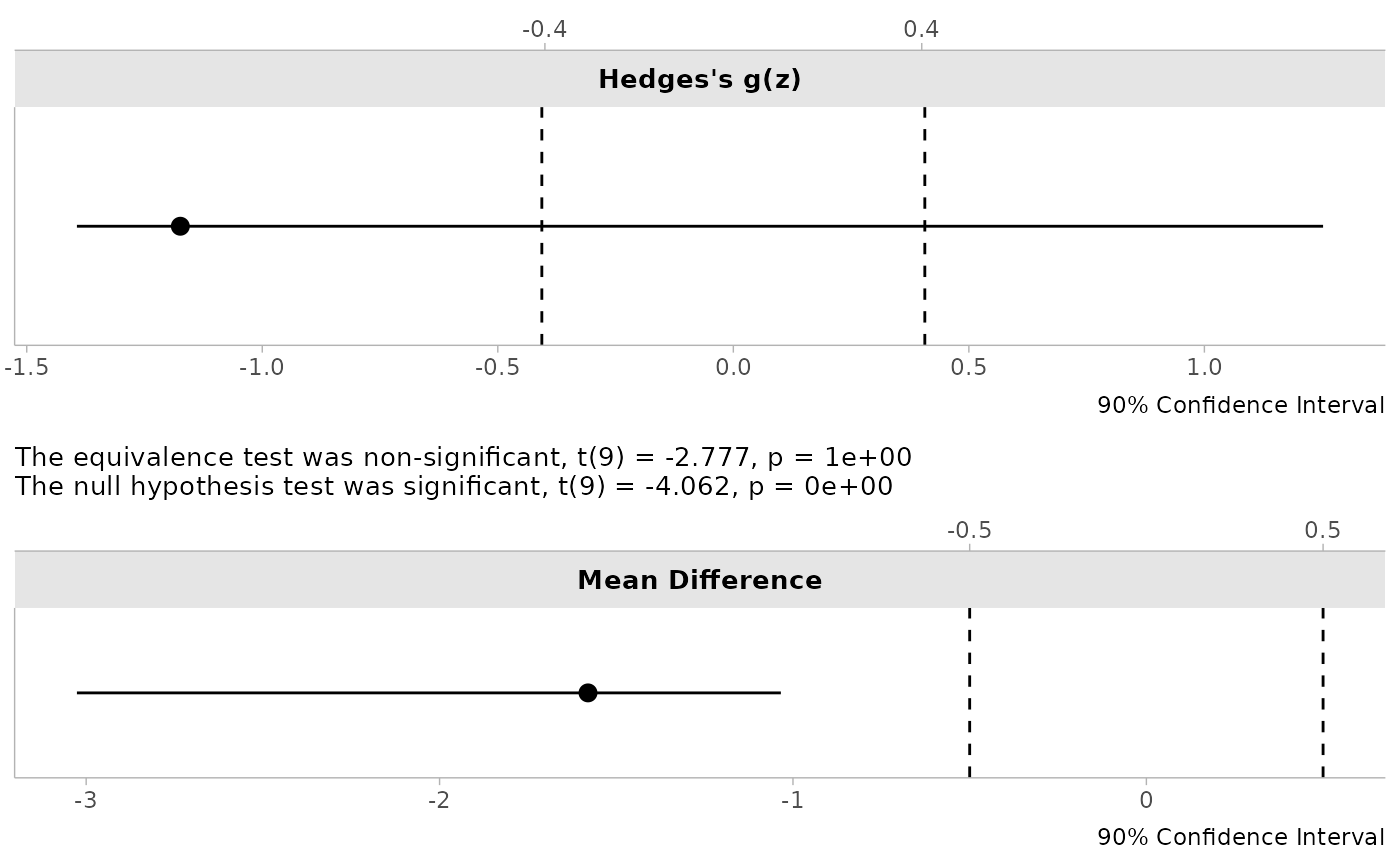

Example

We can use the sleep data to see the bootstrapped results. Notice that the plots show how the re-sampling via bootstrapping indicates the instability of Hedges’s dz.

data('sleep')

# For paired tests with bootstrap methods, use separate vectors

test1 = boot_t_TOST(x = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1],

y = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2],

paired = TRUE,

eqb = .5,

R = 499)

print(test1)##

## Bootstrapped Paired t-test

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant, t(9) = -2.777, p = 1e+00

## The null hypothesis test was significant, t(9) = -4.062, p = 0e+00

## NHST: reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to zero

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## t df p.value

## t-test -4.062 9 < 0.001

## TOST Lower -2.777 9 1

## TOST Upper -5.348 9 < 0.001

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate SE C.I. Conf. Level

## Raw -1.580 0.3786 [-3.0262, -1.0343] 0.9

## Hedges's g(z) -1.174 0.7657 [-1.3935, 1.252] 0.9

## Note: studentized bootstrap ci method utilized.

plot(test1)

Interpreting Bootstrap TOST Results

When interpreting the results of boot_t_TOST:

- The bootstrap p-values (

p1andp2) represent the empirical probability of observing the test statistic or more extreme values under repeated sampling - The confidence intervals are derived directly from the empirical distribution of bootstrap samples

- The distribution plots provide visual insight into the variability of the effect size estimate

For equivalence testing, examine whether both bootstrap p-values are significant (< alpha) and whether the confidence interval for the effect size falls entirely within the equivalence bounds.

Comparing Bootstrap and Permutation Approaches

To illustrate the similarities and differences between these methods, let’s apply both to the same dataset:

# Same equivalence test using both methods

data('sleep')

# Bootstrap approach

boot_result <- boot_t_test(extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "equivalence",

mu = c(-2, 2),

R = 999)

# Permutation approach

perm_result <- perm_t_test(extra ~ group,

data = sleep,

alternative = "equivalence",

mu = c(-2, 2),

R = 999)## Note: Number of permutations (R = 999) is less than 1000. Consider increasing R for more stable p-value estimates.

# Compare results

boot_result##

## Bootstrapped Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: extra by group

## t-observed = 0.49465, df = 17.776, p-value = 0.2903

## alternative hypothesis: equivalence

## null values:

## difference in means difference in means

## -2 2

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## -3.0970524 -0.1114282

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 0.75 2.33

perm_result##

## Monte Carlo Permutation Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: extra by group

## t-observed = 0.49465, df = 17.776, p-value = 0.307

## alternative hypothesis: equivalence

## null values:

## difference in means difference in means

## -2 2

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## -3.120 -0.078

## sample estimates:

## mean of x mean of y

## 0.75 2.33Both methods test the same hypothesis and should yield similar conclusions. Key differences to note:

- P-values: May differ slightly due to Monte Carlo variability and the different resampling mechanisms

- Confidence intervals: Bootstrap uses the resampled effect distribution; permutation uses the percentile method on permuted effects

- Exact inference: When sample sizes are small enough, permutation provides exact p-values with no Monte Carlo error

Summary: Choosing Between Methods

| Feature | Permutation (perm_t_test) |

Bootstrap (boot_t_TOST) |

|---|---|---|

| Resampling type | Without replacement | With replacement |

| Exact p-values possible | Yes (small samples) | No |

| Trimmed means support | Yes (tr argument) |

No |

| Effect size plots | No | Yes |

| Best for | Small samples, exact inference | Moderate samples, visualization |

For very small samples where exact permutations are feasible,

permutation testing is generally preferred because it provides exact

p-values (i.e., no need to set a seed). For larger samples or when you

want the visualization capabilities of boot_t_TOST,

bootstrapping is a good choice. When outliers are a concern, using

perm_t_test with trimming combines the benefits of exact

inference with robust location estimation.

Ratio of Difference (Log Transformed)

In many bioequivalence studies, the differences between drugs are compared on the log scale (He et al. 2022). The log scale allows researchers to compare the ratio of two means.

\[ log ( \frac{y}{x} ) = log(y) - log(x) \]

Where: - y and x are the means of the two groups being compared - The transformation converts multiplicative relationships into additive ones

Why Use The Natural Log Transformation?

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)4 has stated a rationale for using the log transformed values:

Using logarithmic transformation, the general linear statistical model employed in the analysis of BE data allows inferences about the difference between the two means on the log scale, which can then be retransformed into inferences about the ratio of the two averages (means or medians) on the original scale. Logarithmic transformation thus achieves a general comparison based on the ratio rather than the differences.

Log transformation offers several advantages:

- It facilitates the analysis of relative rather than absolute differences

- It often makes right-skewed distributions more symmetric

- It stabilizes variance when variability increases with the mean

- It provides an easy-to-interpret interpretable effect size (ratio of means)

In addition, the FDA considers two drugs as bioequivalent when the ratio between x and y is less than 1.25 and greater than 0.8 (1/1.25), which is the default equivalence bound for the log functions.

Applications Beyond Bioequivalence

While log transformation is standard in bioequivalence studies, it’s useful in many other contexts:

- Economics: Comparing percentage changes in economic indicators

- Environmental science: Analyzing concentration ratios of pollutants

- Biology: Examining growth rates or concentration ratios

- Medicine: Comparing relative efficacy of treatments

- Psychology: Analyzing response time ratios

Consider using log transformation whenever your research question is about relative rather than absolute differences, particularly when the data follow a multiplicative rather than additive pattern.

log_TOST

For example, we could compare whether the cars of different

transmissions are “equivalent” with regards to gas mileage. We can use

the default equivalence bounds (eqb = 1.25).

log_TOST(

mpg ~ am,

data = mtcars

)##

## Log-transformed Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant, t(23.96) = -1.363, p = 9.07e-01

## The null hypothesis test was significant, t(23.96) = -3.826, p = 8.19e-04

## NHST: reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to one

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## t df p.value

## t-test -3.826 23.96 < 0.001

## TOST Lower -1.363 23.96 0.907

## TOST Upper -6.288 23.96 < 0.001

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate SE C.I. Conf. Level

## log(Means Ratio) -0.3466 0.09061 [-0.5017, -0.1916] 0.9

## Means Ratio 0.7071 NA [0.6055, 0.8256] 0.9Note, that the function produces t-tests similar to the

t_TOST function, but provides two effect sizes. The means

ratio on the log scale (the scale of the test statistics), and the means

ratio. The means ratio is missing standard error because the confidence

intervals and estimate are simply the log scale results

exponentiated.

Interpreting the Means Ratio

When interpreting the means ratio:

- A ratio of 1.0 indicates perfect equivalence (no difference)

- Ratios > 1.0 indicate that the first group has higher values than the second

- Ratios < 1.0 indicate that the first group has lower values than the second

For equivalence testing with the default bounds (0.8, 1.25): - Equivalence is established when the 90% confidence interval for the ratio falls entirely within (0.8, 1.25) - This range corresponds to a difference of ±20% on a relative scale

Bootstrap + Log

However, it has been noted in the statistics literature that t-tests

on the logarithmic scale can be biased, and it is recommended that

bootstrapped tests be utilized instead. Therefore, the

boot_log_TOST function can be utilized to perform a more

precise test.

boot_log_TOST(

mpg ~ am,

data = mtcars,

R = 499

)##

## Bootstrapped Log Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## The equivalence test was non-significant, t(23.96) = -1.363, p = 9.62e-01

## The null hypothesis test was significant, t(23.96) = -3.826, p = 0e+00

## NHST: reject null significance hypothesis that the effect is equal to 1

## TOST: don't reject null equivalence hypothesis

##

## TOST Results

## t df p.value

## t-test -3.826 23.96 < 0.001

## TOST Lower -1.363 23.96 0.962

## TOST Upper -6.288 23.96 < 0.001

##

## Effect Sizes

## Estimate SE C.I. Conf. Level

## log(Means Ratio) -0.3466 0.08487 [-0.532, -0.1774] 0.9

## Means Ratio 0.7071 0.06060 [0.5874, 0.8375] 0.9

## Note: studentized bootstrap ci method utilized.The bootstrapped version is particularly recommended when:

- Sample sizes are small (n < 30 per group)

- Data show notable deviations from log-normality

- You want to ensure robust confidence intervals

Just Estimate an Effect Size

It was requested that a function be provided that only calculates a

robust effect size. Therefore, I created the ses_calc and

boot_ses_calc functions as robust effect size calculation5. The

interface is almost the same as wilcox_TOST but you don’t

set an equivalence bound.

# For paired tests, use separate vectors

ses_calc(x = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1],

y = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2],

paired = TRUE,

ses = "r")## estimate lower.ci upper.ci conf.level

## Rank-Biserial Correlation 0.9818182 0.928369 0.9954785 0.95

# Setting bootstrap replications low to

## reduce compiling time of vignette

boot_ses_calc(x = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 1],

y = sleep$extra[sleep$group == 2],

paired = TRUE,

R = 199,

boot_ci = "perc", # recommend percentile bootstrap for paired SES

ses = "r") ## Bootstrapped results contain extreme results (i.e., no overlap), caution advised interpreting confidence intervals.## estimate bias SE lower.ci upper.ci conf.level boot_ci

## 1 0.9818182 0 0.02926873 0.8909091 1 0.95 percChoosing Between Different Bootstrap CI Methods

The boot_ses_calc function offers several bootstrap

confidence interval methods through the boot_ci

parameter:

- “perc” (Percentile): Simple and intuitive, works well for symmetric distributions

- “basic”: Similar to percentile but adjusts for bias, more conservative

- “stud” (studentized): uses the standard error of each bootstrap sample, more accurate for skewed distributions

Summary Comparison of Robust TOST Methods

| Method | Key Advantages | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcoxon TOST | Simple, widely accepted | Ambiguous hypothesis; not about means or medians | legacy analyses |

| Brunner-Munzel | Clear interpretation, robust to heteroscedasticity | Computationally intensive with permutation | Stochastic superiority/dominance |

| Permutation t-test | Exact p-values (small samples), supports trimmed means | Computationally intensive for large samples | Mean differences with small samples |

| Bootstrap TOST | Flexible, visualization of effect distributions | Results vary between runs | Mean differences with moderate samples |

| Log-Transformed | Focuses on relative differences, stabilizes variance | Requires positive data | Bioequivalence, ratio comparisons |

Conclusion

The robust TOST procedures provided in the TOSTER package offer reliable alternatives to standard parametric equivalence testing when data violate typical assumptions. By selecting the appropriate robust method for your specific data characteristics and research question, you can ensure more valid statistical inferences about equivalence or minimal effects.

Remember that no single method is universally superior - the choice depends on your data structure, sample size, and specific research question. When in doubt, running multiple approaches and comparing results can provide valuable insights into the robustness of your conclusions.